Of all the wrongdoings of this pandemic, the one that haunts me most is how people are left to die alone. Health-care workers have been heroic throughout all this, but they do not replace the loved ones whom the dying need to be with, and speak with, even if only one last time.

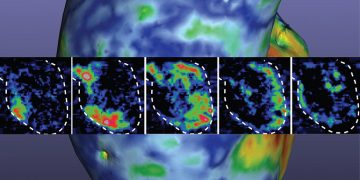

A hallmark of COVID-19 has been the speed with which some patients have crashed, going from feeling only a little sick to being unable to breathe, sometimes in the space of a few hours. Such a crash often necessitates intubation, a process that then renders one incapable of speaking. Many people on ventilators are also heavily sedated and unconscious, to keep them from pulling out the invasive tubes going down their throat. Thus, sometimes with little warning, all communication is lost, and more often than not, a patient is without family or loved ones when this happens.

Early in the pandemic, patients were left alone precisely because the crisis was so dire. Many hospitals outright banned visitors—often even to non-COVID-19 patients. They did not have enough protective gear for the health-care workers, let alone anyone else. Many COVID-19 patients were transported solo in ambulances, and family and friends were unable to join them at the hospital once they had arrived. Others were dropped off by loved ones who were then turned away. Patients sat in their rooms, waiting. If they experienced dyspnea, the acute shortness of breath known as “air hunger,” they crashed alone and terrified.

[Read: The pandemic broke end-of-life care]

Sometimes, a nurse or doctor managed to connect the patient with their loved ones before the tube went in. But dyspnea is a medical emergency, after all, so in many cases there was simply no time for that last call, or anyone available to arrange it. As the disease progressed, families were left clustering around a phone as a hospital worker held up the device for a final goodbye on FaceTime. Often, the family could talk to their loved one, but not vice versa. That’s not enough. What the dying have to say must be heard.

The paramount importance of dying words has long been recognized across cultures. “When a bird is about to die, his song is sad,” Master Tseng, a Confucian leader, says in the more than two-millennia-old Analects of Confucius. “When a man is about to die, his words are true.” In Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates notes how swans sing most beautifully just as they are about to die. That concept of the swan song—one’s last, most beautiful expression—also comes up in Aesop’s fables and in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, and was already a proverb by the third century B.C. In Shakespeare’s Richard II, a dying John of Gaunt, hoping the king will come to hear his last words, says:

O, but they say the tongues of dying men

Enforce attention like deep harmony.

Where words are scarce they are seldom spent in vain,

For they breathe truth that breathe their words in pain

Last words, or “dying declarations” as they are sometimes called, have long been recognized in jurisprudence as out of the ordinary, with known cases going back as early as 1202. That’s why statements uttered by people aware of their impending death can potentially be accepted in court without being subject to “hearsay” restrictions, which ordinarily exclude from evidence assertions made by those not in court to testify in person. In the Middle Ages, it was presumed that people alert to their immediate death would not dare lie, knowing they were about to meet their maker. Death was also seen as removing motives to lie: In a 1789 court case in England, which forms the basis of the modern hearsay exception, the court admitted a woman’s dying words—that her husband was her murderer—as evidence, noting that “when every hope of this world is gone: when every motive to falsehood is silenced,” then “the mind is induced by the most powerful considerations to speak the truth.”

[Read: What people actually say before they die]

The clarity that can come from those facing death is also integral to many modern traditions and philosophies, including the existentialist and psychotherapy schools of thought, which emphasize that death, meaning, loneliness, and freedom are core axes of our lives, and that making all these existential considerations explicit can be key to a good life. The Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl talks about how these “primordial facts” of existence, including our mortality, help us realize and appreciate what truly brings meaning to our lives. The existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom, who specializes in treating people with terminal illnesses, says that terminal cancer, as terrible as it is, gives patients clarity that they did not always have before: “What a pity I had to wait till now, till my body was riddled with cancer, to learn how to live,” a patient lamented. to him Yalom advocates listening to the dying and their wisdom even before we ourselves face our final stretch.

It’s also not just that the dying deserve to be heard or that their wisdom is valuable, but that the living need to have the chance to hear them—to let go on their own, mutual terms. That was something I learned the hard way, when my mother died unexpectedly in her 50s. There is no good way to lose a mother, but my loss was compounded by how complicated our relationship had been as she spiraled into alcoholism later in life. Her drunk version was mean, terrifying, and vicious, although when she was sober, she remained the loving, funny, if quirky, parent I knew as a child. When I moved to the United States, most of our conversations took place over the phone, and I became a human Breathalyzer via voice—a sad talent, I suspect, that I share with other children of alcoholics. Before she even finished saying “Hello,” I knew exactly how drunk she was, and if it was Jekyll-time, I just hung up without fanfare. It never went well if I didn’t.

Then my phone rang early one morning. I jumped out of bed to learn that she had died, without apparent reason—just dropped dead. My mind raced with only one thought: What was our last conversation? Had I hung up on her?

Losing an alcoholic parent can be marked by the same grief anyone feels after losing a parent, especially under tragic circumstances. But it’s also full of regret and guilt in its own ways. The regret is obvious: There is no longer a chance for a final, redemptive chapter. The guilt is layered: Was there anything else one could have done? One more intervention, despite the futility of all the others? And what to do with the feeling of relief from avoiding other, even more feared futures that tangles up with the loss?

[Read: What are the best last words ever?]

In this knot of confusing feelings, though, it was that last conversation that my mind kept circling around for the next many months. The last time my mother called me, she was not only sober; she was in a reflective mood—something that did not happen a lot. She apologized, sort of, for all her drinking and said she was very proud of me. We had a pleasant, lengthy conversation, a rarity that year. She wanted to talk about the latest books she was thinking of translating. She rambled about all the good times, and came back to how happy she was that I was her daughter. It was as close to closure as one could hope for. Intellectually, I knew that it didn’t matter much and that even if I had hung up on her the last time—as I had so many times before—I could have tried to focus on some other good conversation or experience we had shared. I knew it was a stroke of luck that this just happened to be our final conversation. It’s not logical, but that’s how grief works; in the thick of it, the last conversation feels like the truest word.

It’s been six months since the world began battling COVID-19. Coronavirus cases are now surging across the Sun Belt, and hospitals are filling up again. Immediately, some reacted by restricting visitors. Many places had never lifted their restrictions in the first place. Those facing the worst moment of their life still aren’t being treated as a priority.

That dying alone has been normalized, as if it were a small matter, is frightening and inhuman. The panic of the early days of the crisis could be seen as a temporary, terrible compromise. Since then, though, airlines have been bailed out to the tune of many billions of dollars, while there has been no rush to build more negative-pressure rooms, designed to circulate air out, at hospitals, which would allow for much safer visits. We still haven’t developed the infection-control protocols for visitors and built up supplies of personal protective equipment in ways that would avoid the need to completely isolate patients in the days and months ahead.

Even without all the wisdom of the ages, it takes a special kind of inattention to human suffering to not notice how unfortunate this is, that people have been left to face death alone. Some have come to fear dying alone more than the coronavirus itself.

In the years after my mother’s death, I managed to move my focus away from the last conversation and take stock of the good and the bad. I regained perspective, and now I would be at peace with whatever had transpired the last time we spoke, even if I had indeed hung up on her. After a bit of time, I am able to broaden out and consider everything, not just that one last conversation. But that certainly wasn’t always the case. The adage is true: Time has its own healing powers. But that’s not what the people who have lost loved ones to this pandemic should be left with, that time will help with the injustice of having been separated from them at the very end. If society seems to have lost perspective about both compassion and death, all that may be left for us is to reclaim what perspective we can, as best we can.