Editor’s Note: The Atlantic is making vital coverage of the coronavirus available to all readers. Find the collection here.

The United States is once again at risk of outstripping its COVID-19 testing capacity, an ominous development that would deny the country a crucial tool to understand its pandemic in real time.

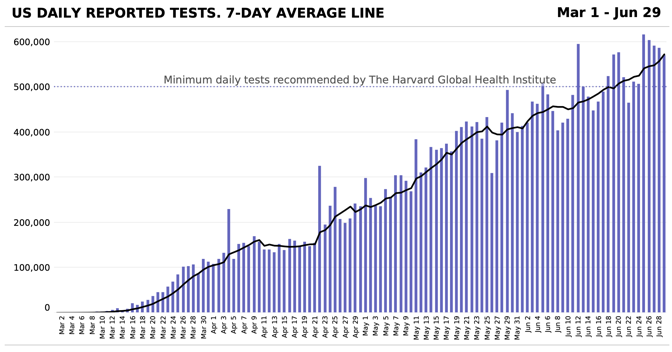

The American testing supply chain is stretched to the limit, and the ongoing outbreak in the South and West could overwhelm it, according to epidemiologists and testing-company executives. While the country’s laboratories have added tremendous capacity in the past few months—the U.S. now tests about 550,000 people each day, a fivefold increase from early April—demand for viral tests is again outpacing supply.

If demand continues to accelerate and shortages are not resolved, then turnaround times for test results will rise, tests will effectively be rationed, and the number of infections that are never counted in official statistics will grow. Any plan to contain the virus will depend on fast and accurate testing, which can identify newly infectious people before they set off new outbreaks. Without it, the U.S. is in the dark.

[Read: A devastating new stage of the pandemic]

The delays have already started. Yesterday, Quest Diagnostics, one of the country’s largest medical-testing companies, said that its systems were overwhelmed and that it would now be able to deliver COVID-19 test results in one day only for hospitalized patients, patients facing emergency surgery, and symptomatic health-care workers. Everyone else now must wait three to five days for a test result.

“Despite the rapid expansion of our testing capacity, demand for testing has been growing faster,” Quest said in a statement last week warning of such a possibility. The company then said that orders for COVID-19 testing had grown by 50 percent in three weeks.

“This is very bad,” Michael Mina, an epidemiology professor at Harvard, told us. Rapid test-turnaround times are the only way to control the coronavirus without forcing every potentially contagious person—everyone who’s had contact with someone diagnosed with COVID-19—into quarantine, he said: “Our modeling efforts more or less show that if you don’t get results back in a day or so, outbreaks really can’t be stopped without isolating and quarantining all contacts preemptively.”

Quest is not the only firm to report growing problems. “We hit the wall three weeks ago,” Jon Cohen, the executive chairman of BioReference Laboratories, a lab-services company that is testing patients for the virus in New York, New Jersey, and Florida, told us. “At that point, most laboratories were already running at capacity, as far as I can tell.”

In mid-June, four changes hit all at once, Cohen said. Large companies began to test their employees en masse, hospitals started to test every patient who needed an elective procedure, and nursing homes started regularly testing their employees and some residents. The American public also seemed to seek out voluntary tests in greater numbers this month. The surge in testing overwhelmed both his testing company’s capacity and its equipment suppliers, he said.

“We not only hit capacity, but any ability to increase our capacity became limited by the supply side,” he said. “The vendors, the suppliers can’t keep up.”

[Read: America is giving up on the pandemic]

LabCorp, another major testing company, also recognized the surging demand for tests in a statement this weekend. “We are doing everything we can to continue delivering results in a timely manner while continually increasing testing capacity,” it said.

Unlike in the first days of the pandemic, when COVID-19 testing kits themselves were in short supply, now the problem lies with the equipment needed to get test results. The hardest-hit new areas do not have enough machines to process samples, leading to a growing backlog of tests, lab directors told us. Some are also running out of the chemical reagent that must react with a testing specimen.

Labs in the U.S. use several different types of viral-testing machines to diagnose COVID-19, and each type has its own supply-chain issues and processing challenges, Lauren Sauer, an emergency-medicine professor at Johns Hopkins, told us by text message. With “so many platforms” in use, she said, resolving bottlenecks and shortages nationwide is especially hard.

“What is currently happening [on testing] is so pocketed and disconnected,” she said.

The American Clinical Laboratory Association, a trade group that represents testing labs, has also warned of shortages. “While our members are collectively performing hundreds of thousands of tests each day, the anticipated demand for COVID-19 testing over the coming weeks will likely exceed members’ testing capacities,” said Julie Khani, its president, in a statement. The group’s members conduct about half of the country’s daily coronavirus tests, according to information in her statement.

The problems have not been felt everywhere. Dina Greene, the director of laboratory services for the health-care group Kaiser Permanente in Washington State, told us that supply-chain problems have not yet disrupted the group’s ability to work. But demand for tests was increasing, she confirmed, and she “wouldn’t be surprised” if shortages hit her team soon.

[Read: ‘How could the CDC make that mistake?’]

Testing has hobbled the American response since the earliest days of the pandemic. As our reporting revealed, the U.S. had tested fewer than 3,000 people for the coronavirus by March 5, even though community spread of the virus had been detected more than a week earlier. In the following weeks, states and hospitals rationed access to tests, granting them only to health-care workers and the sickest patients. This meant that many people who may have had the virus, especially in the Northeast, were never tested for it.

Even after the initial crunch in March, the country’s testing apparatus continued to be beset by problems. For much of April, as the virus killed tens of thousands of Americans, testing plateaued at roughly 150,000 tests a day. Since then, the number of daily tests has increased, but not as fast as experts once hoped. Only in the past two weeks has the U.S. succeeded in testing more than 500,000 people a day, which the Harvard Global Health Institute once said would be a good goal for mid-May. The institute said today that the U.S. must test at least 1.2 million people a day to control the outbreak and at least 4.3 million people a day to eliminate it.

In all that time, the federal government never solved the testing problem. In early April, for instance, researchers at Duke University and the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, called for the government to take charge of the crisis by establishing a task force that would consolidate information about testing and help states and companies understand what was possible. Such a task force could manage emerging shortages, and it could help the country understand how much testing capacity might be attainable by July, August, or September.

But such an effort never took shape. “If this work has been done, I have not seen it, and I fear that neither have the governors and other state and local leaders who are having to make decisions about how and when to reopen,” Caitlin Rivers, an author of the report and a professor at Johns Hopkins University, told Congress last month.

Since then, the Trump administration’s grip on testing has slackened. Brett Giroir, the White House’s testing czar, returned to his day job at the Department of Health and Human Services this month. And at a rally on June 20, President Donald Trump said he told members of his staff to “slow down the testing, please,” because he did not like the growing number of confirmed coronavirus infections. (The president’s staff said afterward that he was joking. After denying for several days that he meant the comment in jest, Trump said last week that he’d been speaking “sarcastically.” Deborah Birx, who is coordinating the White House response to the coronavirus, has said that Trump never asked her to slow down testing.)

“We basically need a Manhattan Project for testing,” Sauer said. “A nationwide, systematic strategy with a clear agency lead is desperately needed. But it’s not happening and I think we all fear significant access issues and supply-chain disruptions in the near future.”

The U.S. is seeing a new surge of cases in the South and West that threatens to overwhelm its health system anew. The country reported more new confirmed COVID-19 cases last week than in any other week of the pandemic so far. While the administration’s focus has drifted elsewhere, demand for tests is only growing. Alex Greninger, a laboratory-medicine professor at the University of Washington, told us that it was little wonder the testing companies were overwhelmed.

“The testing supply chain wasn’t meant for this kind of onslaught of volume across the world at the same time,” he said.